Throughout the numerous commentaries on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra (YS), Vyasa is considered to be the most authoritative analyst, but what if Vyasa misinterpreted the text? What if major points in translation were missed due to a misapplication of the sister philosophy of Sankhya? What if other interpretations of Patanjali’s text are also inaccurate? In this inquisitiveness, spaced from preexisting beliefs about the YS and in consideration of the text from a philosophical view, we will find subtle yet impactful differences between Vyasa’s interpretation and the moral philosophy Patanjali expounds on in the text.

According to Brahmrishi Vishvatma Bawra’s 2018 Samkhya Karika (SK), Sankhya is the dualism of two distinct and independent principles: purusha and prakrti. Purusha is persons: static, passive, and pure consciousness while prakrti is nature; dynamic, made up of the three gunas (tamas, rajas, and sattva) and evolving (Bawra iii). The SK explains that purusha are capable of observing nature and its activities because they are alone and separate from nature (kaivalya), but activity does not take place in purusha. Liberation is achieved with this realization. Purusha holds the characteristics of “witnessing, isolation, indifference, perception, and inactivity” (Bawra 40). In Sankhya, purusha is a neutral observer. Intelligence is the knowledge that purusha is distinct from prakrti, and volition is an attribute of prakrti.

In Sankhya there is no real freedom of choice, agency, or responsibility for the purusha. Sankhya marginalizes dharma (morality), as liberation is attached to the realized distinction between purusha and prakrti, leading to a dispassionate, detached state from the material world and its actions. Sankhya also encourages passivity of purusha in practice, generating spiritual bypassing, or the avoidance and denial of emotional, psychological, social, and systemic issues with an excessive influence on maintaining a positive or “enlightened” state.

Edwin F. Bryant’s commentary, The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (2009), is perhaps the most widely referenced contemporary resource on Patanjali’s text. Bryant regards the metaphysics of Yoga and Sankhya to be the same, but he acknowledges a difference between the methodologies. In his initial commentary, he does not see the YS to be anything philosophical; rather he believes the YS focuses on “the psychological mechanisms and techniques involved in purusha’s liberation” (Bryant 36). This methodology begins with Bryant’s interpretation of YS 1.2: “Yoga is the stilling of the changing states of the mind” (87). Bryant does not understand purusha to be anything more than “pure consciousness” (49). Furthermore, Bryant states “the intellect is the immediate covering of purusha,” by prakrti (59). If a purusha wants to attain liberation, they must “realize pure awareness as an entity distinct and autonomous from the mind (and, of course, body), thought must be stilled and consciousness extracted from its embroilment with the mind and its incessant thinking nature” (59). Bryant believes the translation of Yoga to mean “yoke” is “best avoided in the context of the YS,” as “the goal of Yoga is not to join, but the opposite: to unjoin, that is,to disconnect purusha from prakrti” (81). If one took on this project as Bryant explains it, a purusha would also need to “unjoin” from critical thinking, a potentially harmful action not only for the purusha, but also for other purusha.

Bryant acknowledges Shyam Ranganathan as providing a “sophisticated argument” for purusha possessing agency (Bryant 681). Furthermore, Bryant cites Ranganathan’s argument that dharma must be acknowledged as a key term for morality or ethics throughout Indian philosophy. Bryant writes, “In Sankhya, dharma is a function of buddhi (intellect by way of prakrti), with purusha a mere passive witness. In Yoga, dharma takes on a more active and prescriptive role” (681). Bryant apparently reconsiders his understanding of purusha along with his original claim that the YS is not a text of philosophical inquiry, yet he does not resolve these shifts within his commentary..

Patanjali also takes purusha (including animals) seriously, and thinks a distinction should be made away from prakrti, but Patañjali’s Yoga acknowledges choice, volition, and moral responsibility. Shyam Ranganathan’s 2008 translation of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra presents these three elements of the practice in YS 1.2: “Yogas citta vrtti nirodahah,” or “Yoga is the control of the (moral) character of thought” (Ranganathan 72). Ranganathan maintains the importance and practice of calming thought, but what causes Ranganathan’s translation to stand out – and the majority of interpretations on the YS overlooks – is the complete definition of vrtti.

Vrtti means “rolling down, moral conduct, kind or respectful.” With this translation, Yoga is a moral philosophy. As Ranganathan notes, “The persistent tendency to read philosophers such as Patanjali in light of (Sankhya or Advaita Vedanta) appears thus to be part of the very same colonial influence that has led scholars to conclude that Indian philosophers were not interested in ethics” (25-26). The exclusion of this moral element reduces not only the text, but also how practitioners engage in the practice of Yoga. Without this definition of vrtti, practitioners perpetuate binding thought with their sense of self and they do not really learn or change anything: personally, socially, or systemically.

Morality, then, is innate to liberation. According to YS 3.29, kaivalya (autonomy, an isolated sense of self liberated from samskaras, or latent tendency impressions) occurs when moral uprightness saturates the purusha (dharmameghasamadhi). Ranganathan upholds, “The picture that we receive from the Yoga Sutra is thus that morality reveals the nature of the purusha: in constraining our natural constitution to be moral, we allow the body and mind to reflect the purusha’s true nature and for the purusha to have self-knowledge. Hence, morality is essential to live authentically as a person, in Patanjali’s account” (55). To be moral, purusha (who are diverse) must be allowed the space to be actors in their own lives.

YS 1.2 offers practitioners a choice: do what they have always done, attaching sense of self to thoughts/samskaras thereby limiting their own and others’ wellbeing, or do differently, spacing sense of self from thoughts/samskaras to gather information from different perspectives so as to identify options for thinking, acting, and speaking in a moral manner thereby supporting both their own and others’ wellbeing. Ranganathan’s translation of YS 1.29 validates this: “Hence (one is led) inward to the knowledge of consciousness, intelligence, and volition (the characteristics of the purusha), and also the nullification of the impediments to that knowledge” (102). Consciousness, intelligence, and volition are collectively known as cetana. Yoga, as Patanjali explains it, is the practice of harnessing or yoking (controlling) prakrti (natural tendencies of thought, word, and deed) by employing cetana to align with purusha’s innate morality.

It is obvious and imperative to relinquish interpretation based on Sankhya to Patanjali’s understanding of both purusha and the YS. By way of conscious choice and discernment, the purusha pursues YS 1.2 as an actor, not simply a witness. It is also by way of choice and discernment that a purusha commits their will to Ishvara (the ideal of what it is to be a moral person) rather than to be indifferent. One’s reception of this article, too, is a practice of YS 1.2: disregard this evidence or discriminate between beliefs about the YS and the evidence presented in order to proceed in a moral way?

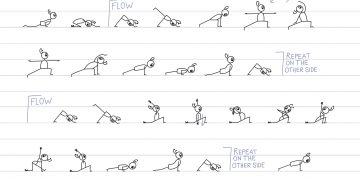

The Sadhana-pada (book of practice) offers the practitioner guidelines, starting with YS 2.1 and the three kriya (tapas, svadhyaya, and Ishvara pranidhana).

Tapas, or austerities, is often misapplied to physical asana (poses), which “should be both still and pleasant” and lead to “continuous effort and endless relaxation” (Ranganathan 198-199), rather than the philosophical aspect of the practice. The practitioner is invited to challenge beliefs, perceptions, and prejudices when tapas applies philosophically to the moral character of one’s being.

Svadhyaya is self study and self-determination, the choice to take a critical stance toward one’s mental life and the subsequent action one’s mentality encourages. It is learning and owning choices. Discernment can be practiced when the turbulence of the mind calms. The mind can then reflect the purusha’s innate morality back on the self so the self can abide in its inherent moral state. Otherwise the mind becomes disrupted and unconstrained and the self understands and identifies itself with mental turbulence.

Ishvara pranidhana is devotion to the ideal of what it means to be a moral person as circumstances shift and demand on that ideal changes. This ideal can be considered best when the mind calms and the sense of self spaces from the pressures of prakrti, which includes one’s mind, body, social circumstances, and relationships. Options can then be observed and dharma can be prescribed and acted upon. Practitioners are challenged to consider how they might act morally not only for themselves, but for all. For those times the practice of the three kriya proves difficult, Patanjali offers support by way of the Eight Limbs.

Meant to be a revolutionary call to practice moral action, Patanjali’s Yoga teaches us that purusha and their choices matter. Ranganathan’s translation presents a functional and realistic philosophy encouraging the practitioner to space one’s sense of self from thought in order to gather information so the practitioner can consider options and enhance wellbeing for all by way of choices. It offers an understanding of liberation neither escapist or selfish, but inherently moral and inclusive of diversity. In light of this evidence, how shall a practitioner proceed?

Mandi King embraces life’s intricacies, navigating its complexities with a caring blend of empathy and humor. As a committed wife and mother of two sons, she finds joy in her family, including her boxer, Ursa. With a personal yoga practice spanning two decades, Mandi began teaching eight years ago, always considering herself a student first and foremost. With a Master’s degree in English Literature, she discovered a profound connection to Yoga’s philosophy. Mandi holds a Level 1 – 100hr certification in Yoga Philosophy, complementing her 200hr E-RYT and YACEP credentials. Currently, she is actively pursuing a Level 2 certification.